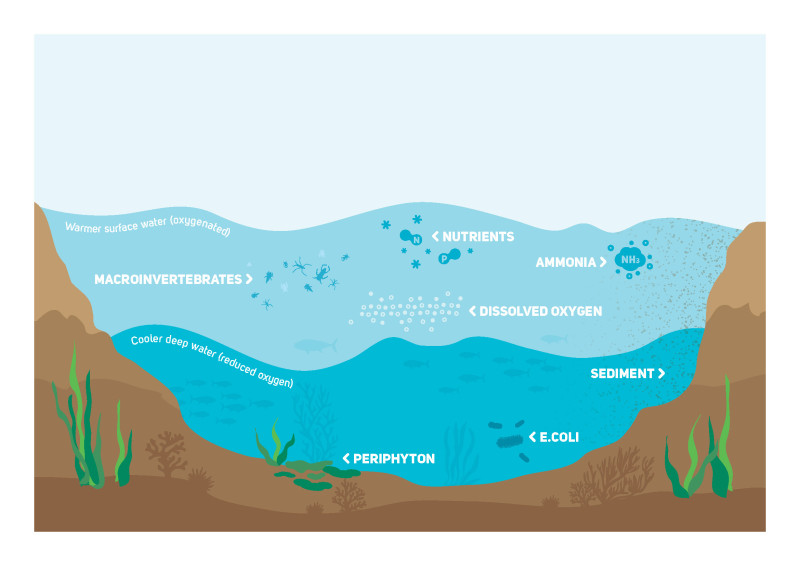

Freshwater Attributes are water quality indicators – such as faecal indicator bacteria (E. coli), dissolved reactive phosphorus, suspended fine sediment (water clarity), nitrate and dissolved oxygen.

These water quality indicators are measured by Tasman District Council during the monthly State of Environment (SOE) river monitoring program

The Tasman District is home to a vast network of freshwater bodies, including:

These waterbodies are more than just bodies of water; they’re vibrant spaces where people come together to live, play, work, and simply enjoy life. Imagine swimming in crystal-clear lakes, fishing for dinner, or simply relaxing on a sandy beach. These places offer opportunities for recreation, sustenance, and community.

The more we understand about out H2O, the better we can meet our responsibilites to protect and improve its health.

Tasman's freshwater environments

Freshwater from the Mountains to the Sea

Periphyton is the algae and slime naturally found on the beds of rivers and streams. The presence of some periphyton is essential for a healthy ecosystem, however excessive growth can negatively affect the waterway.

This proliferation can reduce light penetration, deplete oxygen levels, and disrupt the balance of the aquatic ecosystem.

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for the health and growth of plants and animals in Tasman waterways. It plays a crucial role in supporting the aquatic food chain. Plants, as plants are the primary producers, make this essential nutrient accessible to the animals that consume them. However, excessive nitrogen pollution can have detrimental effects on these waterways, leading to algal blooms, oxygen depletion, and harm to aquatic organisms.

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for the health and growth of plants and animals in Tasman waterways. It plays a crucial role in supporting the aquatic food chain. Plants, as plants are the primary producers, make this essential nutrient accessible to the animals that consume them. However, excessive nitrogen pollution can have detrimental effects on these waterways, leading to algal blooms, oxygen depletion, and harm to aquatic organisms.

The common forms of nitrogen in water are nitrate, nitrite, ammonium and nitrogen gas. Nitrate is a highly water-soluble form of nitrogen. While essential for plant growth, elevated levels can contribute to algae/periphyton blooms.

Aquatic organisms rely on dissolved oxygen in the water for respiration. This oxygen comes from two main sources: it diffuses into the water from the atmosphere and is also produced by photosynthesis in aquatic plants.

The concentration of dissolved oxygen varies with day and night cycles and is influenced by the growth and decay of plants and algae. During the night, plants and algae consume oxygen (they switch from photosynthesis to respiration). The excessive growth of plants or algae leads to an abundance of dissolved oxygen during the day but a scarcity of dissolved oxygen at night.

High concentrations of suspended fine sediment (soil particles) can reduce water clarity, limit light penetration and release nutrients (e.g. phosphorus). This can impact the distribution and abundance of aquatic plants and algae, and some fish species (clogs fish gills and limit ability of fish to feed).

When deposited on the stream bed it can limit the habitat for sensitive invertebrates, while favouring others – altering the natural diversity. In the presence of high nitrogen levels, it can trigger increased growth of algal blooms.

Balancing the effects of sediment is essential for maintaining a healthy and resilient Tasman ecosystem.

E.coli is a group of bacteria that can cause gastro infections in mammals. E.coli is measured not because of a risk to the aquatic life or environment but due to a risk to human health. Monitoring E. coli levels in Tasman waterways is essential for protecting public health and ensuring the safety of recreational activities.

E.coli is a group of bacteria that can cause gastro infections in mammals. E.coli is measured not because of a risk to the aquatic life or environment but due to a risk to human health. Monitoring E. coli levels in Tasman waterways is essential for protecting public health and ensuring the safety of recreational activities.

E.coli is a group of bacteria that are found in the gut and faeces of many animals, including humans.

E.coli levels in water are an indicator of faecal contamination and are monitored primarily due to concerns for human health, rather than impacts on aquatic life or the environment.

E.coli generally spikes after a rainfall event due to effluent being washed into streams and rivers, then settles down as this is flushed through.

E.coli bacteria can manifest in freshwater through various ways, primarily:

Ammonia, a harmful pollutant, can contaminate New Zealand's freshwater bodies. It often enters waterways through agricultural runoff, wastewater discharges, and livestock waste. High levels of ammonia can be toxic to aquatic life, disrupting their respiratory systems and impairing their ability to reproduce.

Ammonia, a harmful pollutant, can contaminate New Zealand's freshwater bodies. It often enters waterways through agricultural runoff, wastewater discharges, and livestock waste. High levels of ammonia can be toxic to aquatic life, disrupting their respiratory systems and impairing their ability to reproduce.

In Tasman waterways, ammonia poses several environmental and ecological challenges:

Ammonia is a harmful pollutant that can have severe consequences for aquatic ecosystems in Tasman. High levels of ammonia can be toxic to a variety of aquatic organisms, including fish, invertebrates, and algae.

This toxicity can disrupt their respiratory systems, impair their growth and development, and ultimately lead to mortality.

Additionally, ammonia can negatively impact ecosystems by reducing dissolved oxygen levels, which can stress and kill aquatic species. It can also alter nutrient balances, favouring harmful algal blooms, and disrupt food webs, leading to a reduction in biodiversity.

Macroinvertebrates are animals without a backbone that are large enough to see without using a microscope. Freshwater macroinvertebrates include insects, snails, crustaceans and worms. Macroinvertebrates help to process organic matter, such as dead leaves, and are a vital food source for fish and birds.

Macroinvertebrates are animals without a backbone that are large enough to see without using a microscope. Freshwater macroinvertebrates include insects, snails, crustaceans and worms. Macroinvertebrates help to process organic matter, such as dead leaves, and are a vital food source for fish and birds.

Macroinvertebrates are small aquatic animals that live on or near the streambed in Tasman's waterways.

They are diverse creatures, ranging from insects to snails, worms, and crustaceans, and are often visible to the naked eye. These organisms play a crucial role in processing organic matter in streams, feeding on periphyton, macrophytes, dead leaves, and wood.

Macroinvertebrates are a vital food source for animals higher up the food chain, such as wading birds and fish. As they mature, many macroinvertebrates emerge from the water and become food for terrestrial animals like birds, bats, and spiders.

If water temperatures in Tasman's waterways exceed their usual range for extended periods, aquatic plants and animals can experience stress and mortality. Low elevation streams and rivers in the region typically have water temperatures that fluctuate between 10°C and 20°C throughout the year.

However, alpine or spring-fed streams can be much colder, while unshaded shallow streams may reach temperatures as high as 30°C during peak summer.

Taking too much water from rivers and streams, can also increase water temperatures due to reduced flow and decreased cooling capacity.

Last modified: