There are over 100 different soil (sub)types in the Tasman Region – from stony soils on the river plains to those where iron has moved through the soil profile for thousands of years. Every soil is unique and comprises a set of individual properties. Some soils, like the stony ones, are great for groundwater recharge. Rainwater infiltrates and moves through the soil profile easily following gravity whereas soils of finer texture, particularly when enriched in organic matter and a little bit of clay, help plants flourish and might also be very suitable for more intensive agricultural production. Disentangling the different properties of soil and explaining what these mean for land management are important tasks for soil and land scientists at Council.

Our latest round of soil mapping work has included covering around 80,000 ha.

It is all worth the effort – the work we are undertaking and the information gained will be used to complement the national soil map of New Zealand.

We recently completed mapping in the Moutere area and are expecting remaining area in Tapawera mapped by end of this year.

Landowners will be contacted by members of the field team in advance if their soil is of interest. Soil mapping is a largely non-invasive procedure, often involving just a visual assessment of a sample taken with a soil auger, which is then replaced.

Further information can be found here: Tasman S-map extension >> New Zealand Soils Portal - Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research.(external link)

Information for landowners

Landcare staff may need to enter private properties for this work.

The soil mapping team will always endeavour to knock on your door first. Landcare staff are well-trained and aware of farm and property health and safety aspects. Animal paddocks will not be accessed, and gates will be left as found. If landowners are not at home, a note by the door or in the letterbox will show we have visited.

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact [email protected].

The mapping campaign is part of a five-year project (2021-2025), co-funded by MPI. Site data will be shared with cooperating landowners and resulting soil maps at a scale of 1:50.000 are made freely available online on the national soil map (Smap) portal.(external link) You can create a free login to access this site. Individual property data and landowner details from those participating in the soil surveys are not visible on Smap or identifiable in any other way.

The productive land in the Tasman is under pressure. Urban life crawls into areas previously used for agriculture, soil health is in decline, and other human needs such as the extraction of raw materials conflict with keeping land and soil resources maintained. Councils all around Aotearoa follow a new National Policy Statement for Highly Productive Land (NPS-HPL) taking effect from 2022, which is set-up to safeguard productive land from further fragmentation. What many might not know is that the Tasman District Council already developed its own classification scheme independent of the NPS-HPL in 1994. The Tasman version is called Productive Land Classification, in short PLC. The PLC was reviewed in 2021 and one task for the land team is to now quantify how the Tasman PLC and the NPS-HPL compare.

Download the 1994 PLC (pdf 5.8 MB)

Download the 2021 PLC (pdf 6.8 MB)

Knowledge about the state of our soils is crucial for understanding how land use and management affect soil. To assess changes in soil quality, Council carries out repeated monitoring at a total of 35 sites with the next sampling for all these sites due in spring 2023. Apart from keeping busy in the fields, the land team is currently revising its soil monitoring programme to better match the national guidelines.

Our team is inspired by the Māori proverb whatungarongaro te tangata toitū te whenua – while the people come and go, the land endures. To highlight the importance of land and soil as a taonga of all our and the environment’s well-being, we like to raise the awareness with the public. Our approach is to simply make visible what otherwise remains hidden underground.

If you would like to help us with our soil mapping and monitoring by providing access to your land or sharing interesting soil data please contact us.

This video gives an insight into the work that's being done and it's importance.

Some may call it ‘dirt’ but in fact soil is the living mantle of the Earth.

Soil is the medium that connects atmosphere (air), hydrosphere (water), lithosphere (bedrock) and biosphere (flora and fauna) all with one another. Soil is the outer, thin coat of the planet reaching from millimetres to a few metres depth. Nearly half of the soil is made up of mineral particles. The rest are varying amounts of air, water and organic compounds depending on the environmental conditions.

Soil is an amazing bioreactor: It can store or release carbon. Pollutants are filtered out of rainwater by soil. Thousands of bacteria and fungi call soil their home. Did you know that soil may even contain more than 10,000 different species per square metre?

Scientists estimate that soil organisms make up more than 25% of the total biodiversity of the planet. Just imagine how vivid the life underneath our feet must be. How intricate the underground soil food webs are and the highways of hyphae shuttling carbon and nutrients back and forth from fungi to plant roots – and vice versa. Some define soils as one of the most complex biomaterials on Earth and indeed soils are complex matter. Although soil scientists tend to distinguish soil by its properties and describe the array of soil types by different names, soil is a continuum. In the landscape, one soil often grades into another. How smooth or distinct this transition between soils might be depends on the factors contributing to soil formation, such as: time, climate, bedrock geology, flora, fauna, and don't forget more recent human impacts and modifications. Soils are mirrors of the present and past with their stories written into different soil horizons. These are layers of soil with a different set of properties such as a different texture or often also a difference in colour.

Interested in getting to know more about soil?

If you'd like to read the full story, take a look at Pātaka Oneone, the New Zealand SoilsPortal. The portal is an amazing resource for all soil-related information. It provides an overview not only about how soils form, different soil types or the most recent science but also explains what soil maps are freely accessible and how soil legacy data can be found.

Reference sites and documents

The State of Knowledge of Soil Biodiversity

The history of mapping soils in the Tasman District reaches back to more than a hundred years and does comprise some impressive pieces of pioneer work. Few know, for example, that one of the oldest New Zealand soil maps – the Soil Map of Waimea Plains (Nelson) – was created by the Cawthron Institute in the 1920s. The Tasman soil legacy also comprises maps from the former tobacco industry and surveys undertaken by the New Zealand Soil Bureau in the mid-20th century. Some of the old maps have already been digitalised by Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research and are freely available online on the Legacy Map Viewer. Maps that have not yet made their way into the digital world are archived in Lincoln but are indexed in a Digital Library and may be digitalised upon request.

More recent mapping work was conducted by Paul Nelson (2003) and Dr Iain Campbell (2005-2018) including thousands of soil auger and pits, let alone 4,494 observations in the Waimea Plains. Iain’s work comprised soil surveys at the farm scale with soil names referring to the ‘old’ Genetic New Zealand taxonomy. Note that this former classification is still common among farmers but differs from the ‘new’ New Zealand Soil Classification. The results of Iain’s work were translated into the new soil taxonomy and are now integrated and available on Smap, the national soil map server (login required). In addition, detailed reports describing the soils of these areas are available:

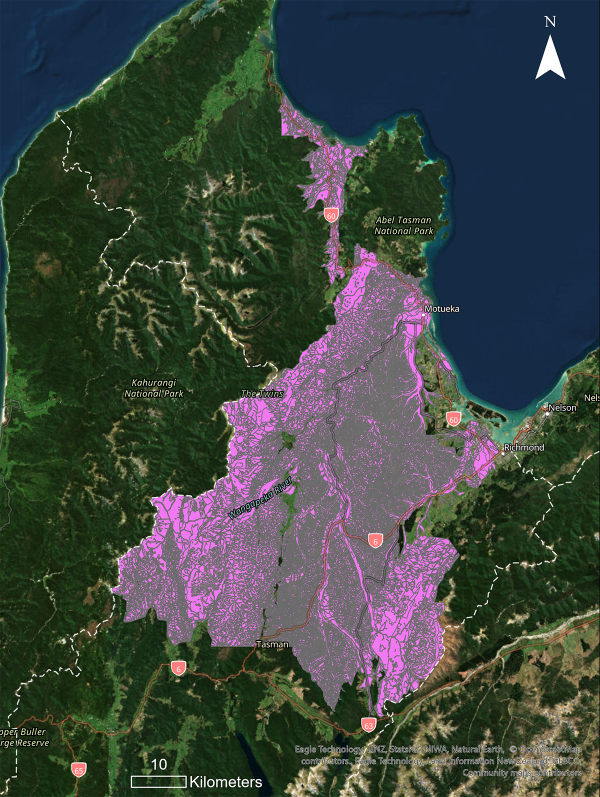

Smap is the most recent digital soil map of Aotearoa New Zealand. The survey work is still on-going and the project is a cooperation between Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research and Councils, co-funded by the Ministry of Primary Industries. As of 2021, 67.7% of the New Zealand land area under agricultural use has been mapped. For the Tasman District, however, Smap data only covers 27% of the effective land area (water bodies and estuaries excluded).

The work itself includes a visual assessment of the soil and small soil pits. Samples might be taken to better characterise soil properties, but permission will always be sought with the landowner in advance. The Smap project seeks to expand on the knowledge of soil resources in New Zealand and data is freely available for registered users. A very useful feature of Smap is so-called ‘soil factsheet’ which provide a detailed description of relevant soil properties for each map polygon.

Tasman region Smap coverage

You can open the map in a new window here.

You can see an example of a soil factsheet here. (pdf 398 KB)

Soil quality is an indicator for how well soil is functioning. Soil scientists interpret the ‘functioning’ of soil as its capability to provide a range of different ecosystem services that humans can use.

One important soil function, for example, is the ability of soil to store, filter and transform nutrients and water. The ecosystem services that humans may subsequently receive from the soil are the production of biomass and food but also important regulating services such as flood mitigation, detoxification of pollutants and carbon sequestration. Using multiple soil ecosystem services to the same extent is not always possible and can lead to conflicts. The Waimea Plains are a good example in that the well-drained soils promote groundwater recharge. However, when used for intensive agricultural production at the same time leaching of nutrients and pollutants can occur. Prioritising one soil ecosystem service over another is, of course, not an easy undertaking but we need to be more aware of the effects that a certain land use has on soils. Monitoring soil quality quantifies these effects and can help decision making about land use and land management.

Council is committed to monitor soils as part of its State of the Environment (SoE) reporting under the Resource Management Act 1991. Soil quality monitoring in Tasman was initiated in 2001 as part of the Ministry of the Environment’s ‘500 Soils Project’. The initial project comprised ten sites, but additional sites were added in the following years (2005, 2009, 2014, 2023) lifting the total number of monitoring sites to 37.

Given how complex soil is, it is not possible to describe soil quality by using a single indicator. Instead, scientists had to choose from an array of different measures. To help quantification, biological, chemical and physical indicators were distinguished and eight key indicators, called SINDI, selected to describe soil quality in New Zealand.

These are: 1) mineralisable soil nitrogen, 2) total soil carbon and nitrogen, 3) soil pH, 4) Olsen phosphorous (P), 5) trace elements, 6) dry bulk density, 7) macroporosity, and 8) aggregate stability.

Read more about soil monitoring guidelines.

To date, the following reports on the state and quality of Tasman soils are available:

One centimetre of topsoil can be lost in seconds whereas it takes fertile soil half a millennium to form naturally. Blown and washed away by the natural elements, covered in concrete or otherwise overutilised by human activities – soil is easily lost or degraded if we do not take care. Yet, looking after soil, farming it sustainably and maintaining or even enhancing its quality make great sense. Keeping soil healthy will contribute to the quality of our food. Safeguarding soil structure, prevents overland flow and erosion. No matter the scale, whether on farm or in your garden, there are a number of things you can do to foster soil quality. Here are some ideas to start with:

Keeping soil alive

Covering soil with concrete will stop important soil processes and prevent the flow of air, water and nutrients through the soil profile. Keeping as much soil uncovered as possible is crucial even on private properties. Just think about how your driveway might look like. What is the degree of surface sealing? Can you use different covers to allow water and air to percolate through your soil?

Synthetic fertiliser, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides – the application of chemicals has adverse effects on the life in your soil and triggers changes in the microbial community structure if not cause soil microbes to die. So best to avoid chemical alterations.

Getting soil fertility right

The more intensive a soil is used the more alterations it is likely to experience and the more important is regular soil testing. Laboratory analyses will help you to get to know more about the state of your soil and any changes of your soil quality and fertility with time. Soil analyses help you to better define what amendments or fertilisers your soil might need and in what quantities. To ensure putting on appropriate amounts, you should undertake a nutrient budget. Ask your fertiliser representative for inputs but be aware that required nutrient inputs will also depend on your farming philosophy (e.g., regenerative, organic, conventional) and the environmental objectives you want to achieve.

Maintaining soil organic matter

Organic matter in soil is an all-rounder. It helps gluing soil particles together, serves as an energy source for soil microbes and includes the majority of soil organic carbon. Maintaining the organic carbon pool in your soil can be done e.g., by first growing and then mulching annual cover crops into the soil between crop cycles. Also, you can grow your own compost from organic materials, food scraps, cuttings, and manure to enrich your soil and help it store nutrients and water, improving soil structure. After cultivation or pasture-renewal, do not keep your soil uncovered and reseed as quickly as possible. The soil is prone to erosion when uncovered and will start to lose carbon as soon as vegetation coverage is removed.

If you want to know how to re-carbonise your soil, take a look at these manuals collated by the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) in 2021, a great inspiration. Soils are our greatest allies in times of climate and environmental change.

Looking after soil structure

The architecture of soil is three-dimensional. Mineral particles form the foundation, but the gaps (soil pores) are filled with water, gases and life. Pugging and compaction of soil alter this structure and often result in poor water infiltration, drainage, and gas exchange. Crop yields will be compromised in a compacted soil and overland flow will be increased. To protect your soil structure from degrading, take care to not graze paddocks at high intensity when the soil is wet or work the soil with heavy machinery. Keep the soil surface covered by vegetation, especially in the wet season and when rainfall is anticipated. Vary cultivation depth to avoid the formation of plough pans.

Examples of a nicely structured, crumbly topsoil under extensively grazed pasture (above) and a topsoil where the structure is compromised by frequent cultivation (below).

The world of soils is inspiring and information plentiful. If you are interested in broadening your horizon, learn more about soils, read a textbook or take a look at what is available on the world-wide-web. Be inspired by the following: